Loneliness across time and space

People feel lonely when their social needs are not met by the quantity and quality of their social relationships. Most research has focused on individual-level predictors of loneliness. However, macro-level factors related to historical time and geographic space might influence loneliness through their effects on individual-level predictors. In this Review, we summarize empirical findings on differences in the prevalence of loneliness across historical time and geographical space and discuss four groups of macro-level factors that might account for these differences: values and norms, family and social lives, technology and digitalization, and living conditions and availability of individual resources. Regarding historical time, media reports convey that loneliness is on the rise, but the empirical evidence is mixed, at least before the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding geographical space, national differences in loneliness are linked to differences in cultural values (such as individualism) but might also be due to differences in the sociodemographic composition of the population. Research on within-country differences in loneliness is scarce but suggests an influence of neighbourhood characteristics. We conclude that a more nuanced understanding of the effects of macro-level factors on loneliness is necessary because of their relevance for public policy and propose specific directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Perceptions of social rigidity predict loneliness across the Japanese population

Article Open access 27 September 2022

Social activity promotes resilience against loneliness in depressed individuals: a study over 14-days of physical isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia

Article Open access 03 May 2022

Both people living in the COVID-19 epicenter and those who have recently left are at a higher risk of loneliness

Article Open access 30 November 2023

Introduction

People experience loneliness when they feel that their social relationships are deficient in terms of quantity or quality and perceive a gap between their actual and desired relationships 1 . Around the world, people describe loneliness as a painful, sometimes agonizing, experience 2 . Loneliness is conceptually distinct from being alone (a momentary state of objective absence of other people), solitude (when being alone is perceived as pleasant and sought out intentionally) 3 and social isolation 1,3,4,5 (the objective lack of social relationships and social contact 1 ).

Through its adverse effects on sleep, immune functioning and health behaviours, loneliness can lead to long-term health issues such as an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases and reduced longevity 1,6,7,8,9 . The health-related consequences of loneliness are detrimental for individual well-being and come with substantial economic costs for society 10,11 . Loneliness has therefore been recognized as a public health issue that needs to be addressed by public policy 12,13 . Indeed, loneliness is on political agendas in the United Kingdom 14 , Germany 15 , Japan 16 and the European Union 17 . Thus, loneliness has important societal implications, and there is a need for evidence-based recommendations for public policy.

Despite these societal implications, loneliness is a deeply subjective experience and almost all empirically established predictors of loneliness refer to characteristics of the person (Table 1). Loneliness is more common among individuals with low socioeconomic status 18,19 and poor health 19,20 , two individual factors that limit people’s opportunities to participate in everyday social activities. Because poor health is particularly common among the elderly, old age is sometimes considered a critical risk factor for loneliness. However, although studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic found that average loneliness was highest in the oldest age group (80 years and older) 18,21,22,23 , increased loneliness has also been reported in younger age groups 18,24 , and a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found no significant relationship between age and loneliness 25 . Identifying with a group that is marginalized within a society (for example, ethnic/racial 26,27 or sexual orientation/identity 28,29,30,31 minority groups) is associated with higher average levels of loneliness, presumably because these groups are more likely to experience stressors such as discrimination or rejection, which increase the risk of loneliness 29,30,31,32,33 . Loneliness is also correlated with personality traits. Individuals high in extraversion and emotional stability are less prone to loneliness than individuals low on these traits 34 . Finally, the characteristics of one’s social relationships are among the most proximal predictors of loneliness. Having a romantic partner, a large social network, frequent social interactions, and high-quality relationships decrease the risk of loneliness 19,20,35,36 .

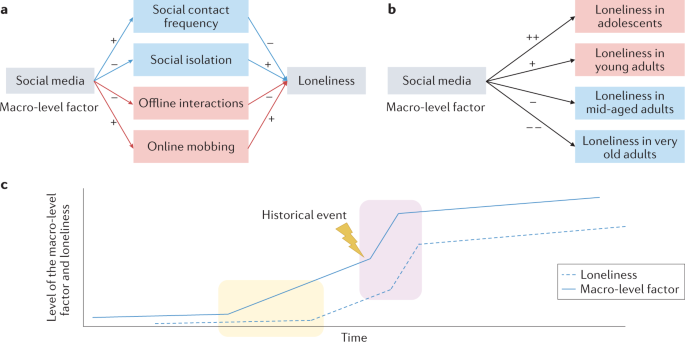

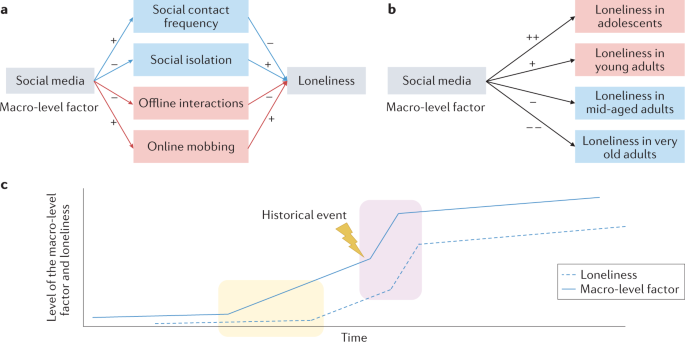

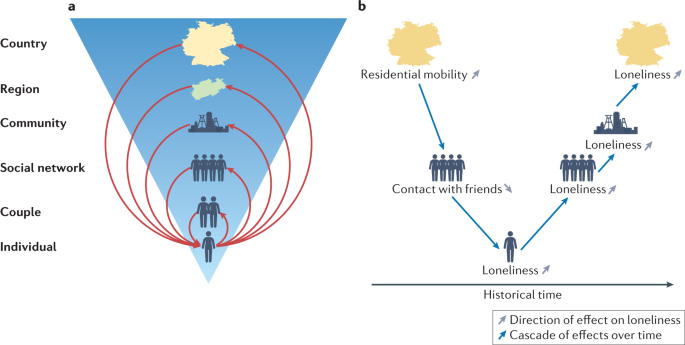

Second, the strength and even the direction of the effect of a macro-level factor on loneliness might differ among different subgroups (Fig. 1b). In population-level studies, these subgroups are collapsed, so strong effects that exist in only some subgroups might be overlooked. For example, social media use appears to be more beneficial for older adults than for adolescents and young adults 81 , but this differential association would not be detected if these groups were analysed together.

Third, the effects of most macro-level factors might unfold over long timescales 39 , so effects on loneliness might be weak, slow and delayed (that is, only detectable after a certain time lag; Fig. 1c). The exact temporal course of these effects is unclear, but it is possible that many macro-level factors require decades to affect population levels of loneliness in an observable way because their effects are weak initially but accumulate over time 140 .

Implications for policy

A better understanding of how macro-level factors influence loneliness across historical time and geographic space is necessary to develop evidence-based recommendations for public policy measures against loneliness. For researchers, this is an invitation to study these factors more systematically in future research. But loneliness has also become a public policy issue in the past 5 years, and policymakers cannot wait for science to reach some consensus. For those who require guidance now, we offer some tentative policy implications.

First, the impact of macro-level factors should not be overestimated: even on the individual level, the causes of loneliness are complex and idiosyncratic. This is probably even more true for the effects of macro-level factors on population levels of loneliness. Attempts to pin some perceived uptick in loneliness to highly specific macro-level factors such as the introduction of smartphones 141 are likely to overestimate the relevance of a single factor, at the peril of drawing attention away from other factors that are at least as important. Instead, public policy is probably most effective if it targets individual risk factors such as poverty and unemployment and provides funding for the development and dissemination of individual-level evidence-based interventions against loneliness. Several reviews provide overviews of effective interventions for different target populations 142,143,144 .

At the same time, the importance of macro-level factors should not be underestimated. Shifts in macro-level factors such as demographic changes or changes in norms and values can influence the risk of loneliness in a population, albeit through complex and still poorly understood pathways. Geographical differences in the distribution of these macro-level factors can help to identify regions that might be particularly at risk and could serve as model regions for testing specific policies. Macro-level trends can therefore provide some tentative information on whether loneliness might become a greater (or lesser) concern in the future.

Finally, macro-level factors might moderate the effects of individual-level predictors on loneliness 42 . For example, the protective effect of being married might depend on the social norms related to marriage at a particular time period or in a particular geographical region 78 . Thus, the efficacy of policies aiming at reducing loneliness by strengthening marriages will vary across historical time and geographical space. This also means that both individual-level and macro-level measures against loneliness have to fit into the greater context. Policies that are applied in different historical or geographical contexts are not necessarily as effective as in the original setting and therefore need to be re-evaluated and, if necessary, adapted.

Summary and future directions

Systematic effects of macro-level factors on loneliness are theoretically plausible but difficult to detect. Macro-level factors tend to have weak effects on individual-level psychological phenomena, particularly if their effects are directly contrasted against individual-level predictors 140 . However, this does not mean that macro-level factors should be dismissed: the effects of macro-level factors often accumulate over time 140 , influence individual-level constructs through multiple indirect (sometimes contradicting) pathways, and might have divergent effects on different subgroups.

To achieve a more nuanced and complete picture of the association between macro-level factors and loneliness, it is necessary to broaden the available database. Representative samples are key to drawing valid conclusions about differences in population levels of loneliness across time or space. Representativeness can be restricted unintentionally through methodological factors (such as nonresponse bias 56,109 ) and intentionally (such as by excluding certain subgroups from the population of interest). For example, many panel studies deliberately exclude residents of care homes, yet this group faces substantial risk for loneliness 145 . Future research must include individuals from groups, regions and countries that have been underrepresented or completely excluded from previous studies.

To study macro-level factors systematically, researchers must routinely collect multilevel data on the social network, neighbourhood and region in which their participants are embedded. Many individual-level predictors can be aggregated at higher levels. For example, the availability of individual resources can be studied at the individual level (for example, how is individual income related to loneliness) as well as at the local, regional and national level (for example, how are local, regional or national poverty rates related to loneliness levels). In addition, future theoretical and empirical work needs to consider genuine macro-level factors, that is, factors that can only be conceptualized and measured at the macro level (for example, the extent to which mental health is prioritized in a health-care system).

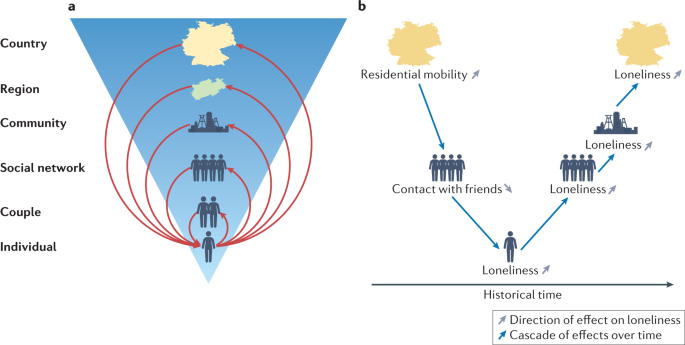

Collecting data repeatedly at regular intervals (for example, annually) over multiple years or even decades would allow systematic investigations into the causal dynamics through which macro-level factors are linked to loneliness. Although most theories and empirical studies treat macro-level factors as predictors of loneliness, the association between macro-level factors and individual-level loneliness is most probably bidirectional (Fig. 2a). The effects of loneliness on individual economic, physical and psychological well-being can translate into population-wide outcomes such as reduced life expectancy 6 , increased health-care costs 10,11 , or reduced political participation 146 . Moreover, trends in macro-level factors might be more relevant than their absolute levels. For example, changes in the demographic composition of a population due to high residential mobility might be more predictive of population loneliness than the demographic composition itself 131 , owing to a cascade of indirect effects across multiple levels (Fig. 2b). Such a cross-level process takes time to unfold and can only be detected with longitudinal data in which factors at all levels are measured repeatedly over long periods of time.

A better understanding of the causal relationships between macro-level factors and loneliness is also necessary to identify causal factors that can be targeted by public policy measures to reduce loneliness 147 . Examples of research designs that would allow such causal inferences include randomized control trials on community-level or regional-level interventions. In addition, and contrary to conventional wisdom among psychologists, nonexperimental studies can, under specific circumstances and with specific assumptions, be used for causal inference 148,149 , for example, natural experiments and prospective studies conducted in the context of major historical events 147 , including wars 150 , natural disasters 151 , pandemics 151,152 or economic crises 153 . Indeed, since 2020, researchers have used the COVID-19 pandemic to study the impact of sudden changes in macro-level factors on loneliness 152,154,155,156 .

Finally, a broad database fulfilling these criteria would enable integrative investigations of loneliness across both time and space. The association between a macro-level factor and loneliness always has to be understood in its specific geographic and historical context simultaneously, and, as geographic space or historical time change, so might the relevance of a macro-level factor for changes in loneliness across space and time. In addition, the relationships and interactions among different macro-level factors might also vary across time and space. For example, on the individual level, social class is correlated with the size and function of social networks such that individuals of higher socioeconomic classes tend to view themselves as more independent (rather than interdependent), allowing them to form more diverse and loose social networks 157 . It is possible that similar relationships can be found on the macro level. For example, economic growth could lead to changes in cultural values related to social relationships.

Although there is some overlap between macro-level factors explaining long-term trends in loneliness across historical time and macro-level factors explaining geographical variation in loneliness, few attempts have been made to conceptually or empirically integrate these different perspectives. A recent exception is a spatiotemporal meta-analysis in which historical changes in loneliness among young adults were related to different regional-level characteristics 54 . In general, spatiotemporal meta-analyses expand classic meta-analytic techniques by using spatial and temporal information (that is, considering not only when but also where an included single study was conducted) to explain heterogeneity in effect sizes 158 . Although no significant spatiotemporal associations were found in that particular meta-analysis 54 , this methodological approach might serve as a template for future research examining macro-level factors across time and space simultaneously.

In sum, longitudinal multilevel data from representative samples from multiple countries are necessary to gain a deeper understanding for why loneliness varies across time and space. Collecting such comprehensive data is not feasible for any single laboratory, but with shared resources it is not an impossible goal. In fact, large-scale studies that cover multiple countries across multiple years already exist (for example, the World Happiness Report 159 ), but loneliness is not yet routinely measured in these studies. We therefore call on researchers and funders of large-scale, cross-national panel studies to include standardized measures of loneliness. In addition, we call on researchers around the world to routinely measure loneliness in their studies and thereby contribute to growing the collective database of loneliness across time and space.

References

- Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med.40, 218–227 (2010). This is a comprehensive overview of theoretical and empirical foundations of loneliness research. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Heu, L. C. et al. Loneliness across cultures with different levels of social embeddedness: a qualitative study. Pers. Relation.28, 379–405 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Long, C. R. & Averill, J. R. Solitude: an exploration of benefits of being alone. J. Theory Soc. Behav.33, 21–44 (2003). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Galanaki, E. Are children able to distinguish among the concepts of aloneness, loneliness, and solitude? Int. J. Behav. Dev.28, 435–443 (2004). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Goossens, L. et al. Loneliness and solitude in adolescence: a confirmatory factor analysis of alternative models. Pers. Individ. Differ.47, 890–894 (2009). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.10, 227–237 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkley, L. C. & Capitanio, J. P. Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Bhttps://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Griffin, S. C., Williams, A. B., Ravyts, S. G., Mladen, S. N. & Rybarczyk, B. D. Loneliness and sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Open7, 2055102920913235 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Park, C. et al. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiat. Res.294, 113514 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kung, C. S. J., Kunz, J. S. & Shields, M. A. Economic aspects of loneliness in Australia. Aust. Econ. Rev.54, 147–163 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mihalopoulos, C. et al. The economic costs of loneliness: a review of cost-of-illness and economic evaluation studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.55, 823–836 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cacioppo, J. T. & Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet391, 426 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Holt-Lunstad, J. The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy Aging Rep.27, 127–130 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Government’s work on tackling loneliness. GOV.ukwww.gov.uk/government/collections/governments-work-on-tackling-loneliness (2018).

- CDU/CSU & SPD. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. The Bundesregierunghttps://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/koalitionsvertrag-zwischen-cdu-csu-und-spd-195906 (2018).

- Kawaguchi, S. Japan’s ‘minister of loneliness’ in global spotlight as media seek interviews. The Mainichihttps://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20210514/p2a/00m/0na/051000c (2021).

- Baarck, J. et al. Loneliness In The EU. Insights From Surveys And Online Media Data. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/28343 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2021).

- Luhmann, M. & Hawkley, L. C. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Dev. Psychol.52, 943–959 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y. & Shalom, V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults. A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int. Psychogeriatr.28, 557–576 (2016). This is a comprehensive review of empirical studies on individual-level predictors of loneliness among older adults. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Frank, A. & Naseer, M. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment. Health26, 225–249 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkley, L. C., Buecker, S., Kaiser, T. & Luhmann, M. Loneliness from young adulthood to old age: explaining age differences in loneliness. Int. J. Behav. Dev.46, 39–49 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- van Ours, J. C. What a drag it is getting old? Mental health and loneliness beyond age 50. Appl. Econ.53, 3563–3576 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nicolaisen, M. & Thorsen, K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev.78, 229–257 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Qualter, P. et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.10, 250–264 (2015). This article reviews and expands the evolutionary theory of loneliness and reviews empirical findings on the development of loneliness across the life span. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mund, M., Freuding, M. M., Möbius, K., Horn, N. & Neyer, F. J. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev.24, 24–52 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Madsen, K. R. et al. Loneliness and ethnic composition of the school class: a nationally random sample of adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc.45, 1350–1365 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lasgaard, M., Friis, K. & Shevlin, M. “Where are all the lonely people?” A population-based study of high-risk groups across the life span. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiat. Epidemiol.51, 1373–1384 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Anderssen, N., Sivertsen, B., Lønning, K. J. & Malterud, K. Life satisfaction and mental health among transgender students in Norway. BMC Public Health20, 138 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kuyper, L. & Fokkema, T. Loneliness among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: the role of minority stress. Arch. Sex. Behav.39, 1171–1180 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hughes, M. et al. Predictors of loneliness among older lesbian and gay people. J. Homosex.https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.2005999 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buczak-Stec, E., König, H.-H. & Hajek, A. Sexual orientation and psychosocial factors in terms of loneliness and subjective well-being in later life. Gerontologisthttps://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac088 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Carretta, H. & Terracciano, A. Perceived discrimination and physical, cognitive, and emotional health in older adulthood. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiat.23, 171–179 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhang, M., Barreto, M. & Doyle, D. Stigma-based rejection experiences affect trust in others. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci.11, 308–316 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buecker, S., Maes, M., Denissen, J. J. A. & Luhmann, M. Loneliness and the Big Five personality traits: a meta–analysis. Eur. J. Pers.34, 8–28 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Heinrich, L. M. & Gullone, E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev.26, 695–718 (2006). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkley, L. C. et al. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. J. Gerontol. B63, S375–S384 (2008). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology Of Human Development: Experiments By Nature And Design (Harvard Univ. Press, 1979).

- Bühler, J. L. & Nikitin, J. Sociohistorical context and adult social development: new directions for 21st century research. Am. Psychol.75, 457–469 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Drewelies, J., Huxhold, O. & Gerstorf, D. The role of historical change for adult development and aging: towards a theoretical framework about the how and the why. Psychol. Aging34, 1021–1039 (2019). This article introduces the HIDECO framework. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oishi, S. Socioecological psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol.65, 581–609 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rentfrow, P. J. Geographical psychology. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 165–170 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- de Jong Gierveld, J. & Tesch-Römer, C. Loneliness in old age in Eastern and Western European societies: theoretical perspectives. Eur. J. Ageing9, 285–295 (2012). This article summarizes theoretical perspectives on cross-national differences in loneliness with a focus on European countries. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fiori, K. L., Windsor, T. D. & Huxhold, O. The increasing importance of friendship in late life: understanding the role of sociohistorical context in social development. Gerontology66, 286–294 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I. & Seeman, T. E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med.51, 843–857 (2000). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hertz, N. The Lonely Century: How To Restore Human Connection In A World That’s Pulling Apart (Sceptre, 2021).

- Snell, K. D. M. The rise of living alone and loneliness in history. Soc. Hist.42, 2–28 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Anttila, T., Selander, K. & Oinas, T. Disconnected lives: trends in time spent alone in Finland. Soc. Indic. Res.150, 711–730 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hamamura, T. Cross-temporal changes in people’s ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 17–21 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buecker, S., Denissen, J. J. A. & Luhmann, M. A propensity-score matched study of changes in loneliness surrounding major life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.121, 669–690 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rudolph, C. W., Costanza, D. P., Wright, C. & Zacher, H. Cross-temporal meta-analysis: a conceptual and empirical critique. J. Bus. Psychol.35, 733–750 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Twenge, J. M. The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.79, 1007–1021 (2000). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Clark, D. M. T., Loxton, N. J. & Tobin, S. J. Declining loneliness over time: evidence from American colleges and high schools. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.41, 78–89 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Xin, S. & Xin, Z. Birth cohort changes in Chinese college students’ loneliness and social support. Int. J. Behav. Dev.40, 398–407 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M. & Luhmann, M. Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychol. Bull.147, 787–805 (2021). This article provides the most comprehensive cross-temporal meta-analysis on historical changes in loneliness published to date. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yan, Z., Yang, X., Wang, L., Zhao, Y. & Yu, L. Social change and birth cohort increase in loneliness among Chinese older adults: a cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1995-2011. Int. Psychogeriatr.26, 1773–1781 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stedman, R. C., Connelly, N. A., Heberlein, T. A., Decker, D. J. & Allred, S. B. The end of the (research) world as we know it? Understanding and coping with declining response rates to mail surveys. Soc. Nat. Resour.32, 1139–1154 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ko, S. Y., Wei, M., Rivas, J. & Tucker, J. R. Reliability and validity of scores on a measure of stigma of loneliness. Couns. Psychol.50, 96–122 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Penning, M. J., Liu, G. & Chou, P. H. B. Measuring loneliness among middle-aged and older adults: the UCLA and de Jong Gierveld loneliness scales. Soc. Indic. Res.118, 1147–1166 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Danneel, S., Maes, M., Vanhalst, J., Bijttebier, P. & Goossens, L. Developmental change in loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc.47, 148–161 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- von Soest, T., Luhmann, M. & Gerstorf, D. The development of loneliness through adolescence and young adulthood: its nature, correlates, and midlife outcomes. Dev. Psychol.56, 1919–1934 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hülür, G. et al. Cohort differences in psychosocial function over 20 years: current older adults feel less lonely and less dependent on external circumstances. Gerontology62, 354–361 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Suanet, B. & van Tilburg, T. G. Loneliness declines across birth cohorts: the impact of mastery and self-efficacy. Psychol. Aging34, 1134–1143 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Victor, C. R. et al. Has loneliness amongst older people increased? An investigation into variations between cohorts. Ageing Soc.22, 585–597 (2002). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nyqvist, F., Cattan, M., Conradsson, M., Näsman, M. & Gustafsson, Y. Prevalence of loneliness over ten years among the oldest old. Scand. J. Public. Health45, 411–418 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dahlberg, L., Agahi, N. & Lennartsson, C. Lonelier than ever? Loneliness of older people over two decades. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.75, 96–103 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Eloranta, S., Arve, S., Isoaho, H., Lehtonen, A. & Viitanen, M. Loneliness of older people aged 70: a comparison of two Finnish cohorts born 20 years apart. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.61, 254–260 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schaie, K. W., Willis, S. L. & Pennak, S. An historical framework for cohort differences in intelligence. Res. Hum. Dev.2, 43–67 (2005). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kupper, L. L., Janis, J. M., Karmous, A. & Greenberg, B. G. Statistical age-period-cohort analysis: a review and critique. J. Chronic Dis.38, 811–830 (1985). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Santos, H. C., Varnum, M. E. W. & Grossmann, I. Global increases in individualism. Psychol. Sci.28, 1228–1239 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hofstede, G. Cultures And Organizations. Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, And Organizations Across Nations 2nd edn (Sage Publications, 2001).

- Sanner, C., Ganong, L. & Coleman, M. Families are socially constructed: pragmatic implications for researchers. J. Family Issues42, 422–444 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaspers, E. D. T. & Pieters, R. G. M. Materialism across the life span: an age-period-cohort analysis. J. Personality Soc. Psychol.111, 451–473 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M. & Kasser, T. The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: a meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.107, 879–924 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J. & Lance, C. E. Generational differences in work values: leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J. Manag.36, 1117–1142 (2010). Google Scholar

- Twenge, J. M. & Kasser, T. Generational changes in materialism and work centrality, 1976–2007: associations with temporal changes in societal insecurity and materialistic role modeling. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.39, 883–897 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Riggle, E. D. B. et al. First comes marriage, then comes the election: macro-level event impacts on African American, Latina/x, and White sexual minority women. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy18, 112–126 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ogolsky, B. G., Monk, J. K., Rice, T. M. & Oswald, R. F. Personal well-being across the transition to marriage equality: a longitudinal analysis. J. Family Psychol.33, 422–432 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Böger, A. & Huxhold, O. The changing relationship between partnership status and loneliness: effects related to aging and historical time. J. Gerontol. B75, 1423–1432 (2020). This exemplary empirical study used an elegant design to examine how historical shifts in social norms affect the link between partnership status and loneliness. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- van Tilburg, T. G., Aartsen, M. J. & van der Pas, S. Loneliness after divorce: a cohort comparison among Dutch young-old adults. Eur. Sociol. Rev.31, 243–252 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wang, H. & Wellman, B. Social connectivity in America: changes in adult friendship network size from 2002 to 2007. Am. Behav. Sci.53, 1148–1169 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness and social internet use. Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci.13, 70–87 (2018). This is a comprehensive and nuanced review on the link between social media use and loneliness. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sbarra, D. A., Briskin, J. L. & Slatcher, R. B. Smartphones and close relationships: the case for an evolutionary mismatch. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.14, 596–618 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav.3, 173–182 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H. & Campbell, W. K. Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. J. Soc. Pers. Relat.36, 1892–1913 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hancock, J., Liu, S. X., Luo, M. & Mieczkowski, H. Psychological well-being and social media use: a meta-analysis of associations between social media use and depression, anxiety, loneliness, eudaimonic, hedonic and social well-being. SSRN J.https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4053961 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Orben, A. Teenagers, screens and social media: a narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiat. Epidemiol.55, 407–414 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Andrews, D. & Caldera Sánchez, A. Residential mobility and public policy in OECD countries. OECD J. Econ. Stud.2011, https://doi.org/10.1787/19952856 (2011).

- McAuliffe, M., Khadria, B. & Bauloz, C. World Migration Report 2020 10th edn (IOM, 2019).

- Palinkas, L. A. & Wong, M. Global climate change and mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 12–16 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wrzus, C., Hänel, M., Wagner, J. & Neyer, F. J. Social network changes and life events across the life span: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull.139, 53–80 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Choi, H. & Oishi, S. The psychology of residential mobility: a decade of progress. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 72–75 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oishi, S. & Talhelm, T. Residential mobility. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci.21, 425–430 (2012). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Koelet, S. & de Valk, H. A. G. Social networks and feelings of social loneliness after migration: the case of European migrants with a native partner in Belgium. Ethnicities16, 610–630 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dolberg, P., Shiovitz-Ezra, S. & Ayalon, L. Migration and changes in loneliness over a 4-year period: the case of older former Soviet Union immigrants in Israel. Eur. J. Ageing13, 287–297 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barrett, A. & Mosca, I. Social isolation, loneliness and return migration: evidence from older Irish adults. J. Ethnic Migr. Stud.39, 1659–1677 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oishi, S. et al. Residential mobility increases motivation to expand social network: but why. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol.49, 217–223 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M. & Hansen, N. Far away from home and (not) lonely: relational mobility in migrants’ heritage culture as a potential protection from loneliness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat.77, 140–150 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Crimmins, E. M. & Beltrán-Sánchez, H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J. Gerontol. B66, 75–86 (2011). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mathers, C. D., Stevens, G. A., Boerma, T., White, R. A. & Tobias, M. I. Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. Lancet385, 540–548 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bloom, D. & Canning, D. Global demographic change: dimensions and economic significance. Pop. Aging Human Cap. Accum. Product. Growth34, 17–51 (2008). Google Scholar

- Dykstra, P. A. Older adult loneliness. Myths and realities. Eur. J. Ageing6, 91–100 (2009). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bergstrom, C. T., West & Jevin, D. Calling Bullshit: The Art Of Scepticism In A Data-driven World (Random House, 2020).

- Hansen, T. & Slagsvold, B. Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: results from the Generations and Gender Survey. Soc. Indic. Res.129, 445–464 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vozikaki, M., Papadaki, A., Linardakis, M. & Philalithis, A. Loneliness among older European adults: results from the survey of health, aging and retirement in Europe. J. Public Health26, 613–624 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yang, K. & Victor, C. R. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc.31, 1368–1388 (2011). This is one of the most comprehensive empirical studies on cross-national differences in the link between age and loneliness. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zoutewelle-Terovan, M. & Liefbroer, A. C. Swimming against the stream: non-normative family transitions and loneliness in later life across 12 nations. Gerontologist58, 1096–1108 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Surkalim, D. L. et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J.376, e067068 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stickley, A. et al. Loneliness: its correlates and association with health behaviours and outcomes in nine countries of the former Soviet Union. PLoS ONE8, e67978 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Billiet, J., Koch, A. & Philippens, M. in Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons From The European Social Survey Ch. 6 (eds Jowell, R. et al.) 107–129 (Sage Publications, 2007).

- van Staden, W. C. W. & Coetzee, K. Conceptual relations between loneliness and culture. Curr. Opin. Psychiat.23, 524–529 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rokach, A. The effect of gender and culture on loneliness: a mini review. Emerg. Sci. J.2, 59–64 (2018). Google Scholar

- Hawkley, L. C., Steptoe, A., Schumm, L. P. & Wroblewski, K. Comparing loneliness in England and the United States, 2014–2016: differential item functioning and risk factor prevalence and impact. Soc. Sci. Med.265, 113467 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Maes, M., Wang, J. M., van den Noortgate, W. & Goossens, L. Loneliness and attitudes toward being alone in Belgian and Chinese adolescents: examining measurement invariance. J. Child. Family Stud.25, 1408–1415 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkley, L. C., Duvoisin, R., Ackva, J., Murdoch, J. C. & Luhmann, M. Loneliness in older adults in the USA and Germany: measurement invariance and validation. NORC at the University of Chicagohttps://www.norc.org/PDFs/Working%20Paper%20Series/WP-2015-004.pdf (2016).

- Hawkley, L. C., Gu, Y., Luo, Y.-J. & Cacioppo, J. T. The mental representation of social connections: generalizability extended to Beijing adults. PLoS ONE7, e44065 (2012). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings Psychol. Cult.https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 (2011). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lykes, V. A. & Kemmelmeier, M. What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. J. Crosscultural Psychol.45, 468–490 (2014). Google Scholar

- Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M. & Hansen, N. Lonely alone or lonely together? A cultural-psychological examination of individualism-collectivism and loneliness in five European countries. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.45, 780–793 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barreto, M. et al. Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. J. Soc. Pers. Relat.39, 2658–2679 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kerr, N. A. & Stanley, T. B. Revisiting the social stigma of loneliness. Pers. Individ. Diff.171, 110482 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pescosolido, B. A. & Martin, J. K. The stigma complex. Annu. Rev. Sociol.41, 87–116 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liu, S. S., Morris, M. W., Talhelm, T. & Yang, Q. Ingroup vigilance in collectivistic cultures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA116, 14538–14546 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fokkema, T., de Jong Gierveld, J. & Dykstra, P. A. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl.146, 201–228 (2012). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barreto, M. et al. Loneliness around the world: age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Pers. Individ. Diff.169, 110066 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swader, C. S. Loneliness in Europe: personal and societal individualism-collectivism and their connection to social isolation. Soc. Forces97, 1307–1336 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wong, Y. J., Wang, S.-Y. & Klann, E. M. The emperor with no clothes: a critique of collectivism and individualism. Arch. Sci. Psychol.6, 251–260 (2018). Google Scholar

- Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M. & Hansen, N. Does loneliness thrive in relational freedom or restriction? The culture–loneliness framework. Rev. Gen. Psychol.25, 60–72 (2021). This theoretical article introduces the culture–loneliness framework to explain national differences in loneliness. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- LaRose, R., Connolly, R., Lee, H., Li, K. & Hales, K. D. Connection overload? A cross cultural study of the consequences of social media connection. Inf. Syst. Manag.31, 59–73 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Scharf, T. & de Jong Gierveld, J. Loneliness in urban neighbourhoods: an Anglo-Dutch comparison. Eur. J. Ageing5, 103 (2008). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beer, A. et al. Regional variation in social isolation amongst older Australians. Reg. Studies Reg. Sci.3, 170–184 (2016). Google Scholar

- Buecker, S., Ebert, T., Götz, F. M., Entringer, T. M. & Luhmann, M. In a lonely place: investigating regional differences in loneliness. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci.12, 147–155 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Marquez, J. et al. Loneliness in young people: a multilevel exploration of social ecological influences and geographic variation. J. Public Healthhttps://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab402 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Domènech-Abella, J. et al. The role of socio-economic status and neighborhood social capital on loneliness among older adults: evidence from the Sant Boi Aging Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiat. Epidemiol.52, 1237–1246 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Menec, V. H., Newall, N. E., Mackenzie, C. S., Shooshtari, S. & Nowicki, S. Examining individual and geographic factors associated with social isolation and loneliness using Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) data. PLoS ONE14, e0211143 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Victor, C. R. & Pikhartova, J. Lonely places or lonely people? Investigating the relationship between loneliness and place of residence. BMC Public Health20, 778 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Matthews, T. et al. Loneliness and neighborhood characteristics: a multi-informant, nationally representative study of young adults. Psychol. Sci.30, 765–775 (2019). This is an exemplary study on the role of neighbourhood characteristics in explaining geographical differences in loneliness. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Yu, R., Cheung, O., Lau, K. & Woo, J. Associations between perceived neighborhood walkability and walking time, wellbeing, and loneliness in community-dwelling older Chinese people in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Healthhttps://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101199 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kearns, A., Whitley, E., Tannahill, C. & Ellaway, A. ‘Lonesome town’? Is loneliness associated with the residential environment, including housing and neighbourhood factors? J. Community Psychol.43, 849–867 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Timmermans, E. et al. Social and physical neighbourhood characteristics and loneliness among older adults: results from the MINDMAP project. J. Epidemiol. Community Health75, 464–469 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Götz, F. M., Gosling, S. D. & Rentfrow, P. J. Small effects: the indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.17, 1745691620984483 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Twenge, J. M. et al. Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness. J. Adolesc.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bessaha, M. L. et al. A systematic review of loneliness interventions among non-elderly adults. Clin. Soc. Work. J.48, 110–125 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev.15, 219–266 (2011). This is a comprehensive meta-analysis on loneliness interventions, with a particular focus on which characteristics of interventions are linked to a greater efficacy. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. & Perach, R. Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: a critical review. Am. J. Health Promotion29, e109–e125 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kaspar, R., Wenner, J. & Tesch-Römer, C. Einsamkeit in der Hochaltrigkeit. SSOARhttps://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/77004 (2022).

- Langenkamp, A. Enhancing, suppressing or something in between — loneliness and five forms of political participation across Europe. Eur. Soc.23, 311–332 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jokela, M. Neighborhoods, psychological distress, and the quest for causality. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 22–26 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Grosz, M. P., Rohrer, J. M. & Thoemmes, F. The taboo against explicit causal inference in nonexperimental psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.15, 1243–1255 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rohrer, J. M. Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: graphical causal models for observational data. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci.1, 27–42 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cheung, F. et al. The impact of the Syrian conflict on population well-being. Nat. Commun.11, 3899 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Grossmann, I. & Varnum, M. E. W. Social structure, infectious diseases, disasters, secularism, and cultural change in America. Psychol. Sci.26, 311–324 (2015). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buecker, S. et al. Changes in daily loneliness for German residents during the first four weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med.265, 113541 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bianchi, E. C. How the economy shapes the way we think about ourselves and others. Curr. Opin. Psychol.32, 120–123 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buecker, S. & Horstmann, K. T. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Psychol.26, 272–284 (2021). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Luchetti, M. et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am. Psychol.75, 897–908 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aknin, L. B. et al. Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.17, 915–936 (2022). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Carey, R. M. & Markus, H. R. Social class shapes the form and function of relationships and selves. Curr. Opin. Psychol.18, 123–130 (2017). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Johnson, B. T., Cromley, E. K. & Marrouch, N. Spatiotemporal meta-analysis: reviewing health psychology phenomena over space and time. Health Psychol. Rev.11, 280–291 (2017). This article provides an introduction to spatiotemporal meta-analysis, a method that can be used to study phenomena across space and time simultaneously. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Helliwell, J. F. et al. (eds). World Happiness Report 2021 (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2021).

- Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., van den Noortgate, W. & Goossens, L. Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pers.33, 642–654 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hsieh, N. & Hawkley, L. Loneliness in the older adult marriage: associations with dyadic aversion, indifference, and ambivalence. J. Soc. Pers. Relation.35, 1319–1339 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Coyle, C. E. & Dugan, E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J. Aging Health24, 1346–1363 (2012). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Russell, D. W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess.66, 20–40 (1996). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A. & Cutrona, C. E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.39, 472–480 (1980). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L. & Ma, H. Handbook Of Mental Health Assessment (Chinese Mental Health Journal Press, 1999).

- Hawkley, L. C., Wroblewski, K., Kaiser, T., Luhmann, M. & Schumm, L. P. Are U.S. older adults getting lonelier? Age, period, and cohort differences. Psychol. Aging34, 1144–1157 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Trzesniewski, K. H. & Donnellan, M. B. Rethinking “Generation Me”: a study of cohort effects from 1976-2006. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.5, 58–75 (2010). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Arsenijevic, J. & Groot, W. Does household help prevent loneliness among the elderly? An evaluation of a policy reform in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health18, 1104 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Börsch-Supan, A. et al. Data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int. J. Epidemiol.42, 992–1001 (2013). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beller, J. & Wagner, A. Loneliness and health: the moderating effect of cross-cultural individualism/collectivism. J. Aging Health32, 1516–1527 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging26, 655–672 (2004). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Domènech-Abella, J. et al. The association between socioeconomic status and depression among older adults in Finland, Poland and Spain: a comparative cross-sectional study of distinct measures and pathways. J. Affect. Disord.241, 311–318 (2018). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Leonardi, M. et al. Determinants of health and disability in ageing population: the COURAGE in Europe Project (collaborative research on ageing in Europe). Clin. Psychol. Psychother.21, 193–198 (2014). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas.1, 385–401 (1977). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- de Jong Gierveld, J. & van Tilburg, T. G. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness. Res. Aging28, 582–598 (2006). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fokkema, T., Kveder, A., Hiekel, N., Emery, T. & Liefbroer, A. C. Generations and Gender Programme Wave 1 data collection. Demogr. Res.34, 499–524 (2016). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Reif, K. & Melich, A. Euro-Barometer 37.2: Elderly Europeans, April–May 1992 (ICPSR 9958). ICPSRhttps://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/9958 (2008).

- Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). ESS3 Data Documentation.https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS3-2006 (2018).

- Sauter, S. R., Kim, L. P. & Jacobsen, K. H. Loneliness and friendlessness among adolescents in 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health25, 21–27 (2020). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sundström, G., Fransson, E., Malmberg, B. & Davey, A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur. J. Ageing6, 267 (2009). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). ESS7 Data Documentation.https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS7-2014 (2018).

- Vancampfort, D. et al. Leisure-time sedentary behavior and loneliness among 148,045 adolescents aged 12–15 years from 52 low- and middle-income countries. J. Affect. Disord.251, 149–155 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vancampfort, D. et al. Physical activity and loneliness among adults aged 50 years or older in six low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiat.34, 1855–1864 (2019). ArticleGoogle Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Faculty of Psychology, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany Maike Luhmann, Susanne Buecker & Marilena Rüsberg

- Maike Luhmann