Written by Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

| September 5, 2023

Reviewed by Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

A behavioral objective is a clear, specific, and measurable statement of what a learner is expected to achieve at the end of a unit of work.

It describes the desired outcome in terms of the learner’s behavior, specifying the knowledge, skills, or attitudes that the learner should acquire.

When writing a curriculum, educators need to state the behavioral objectives as a way to outline the goal behaviors that will demonstrate successful completion of the unit of work.

Contents showBehavioral objectives are important because they:

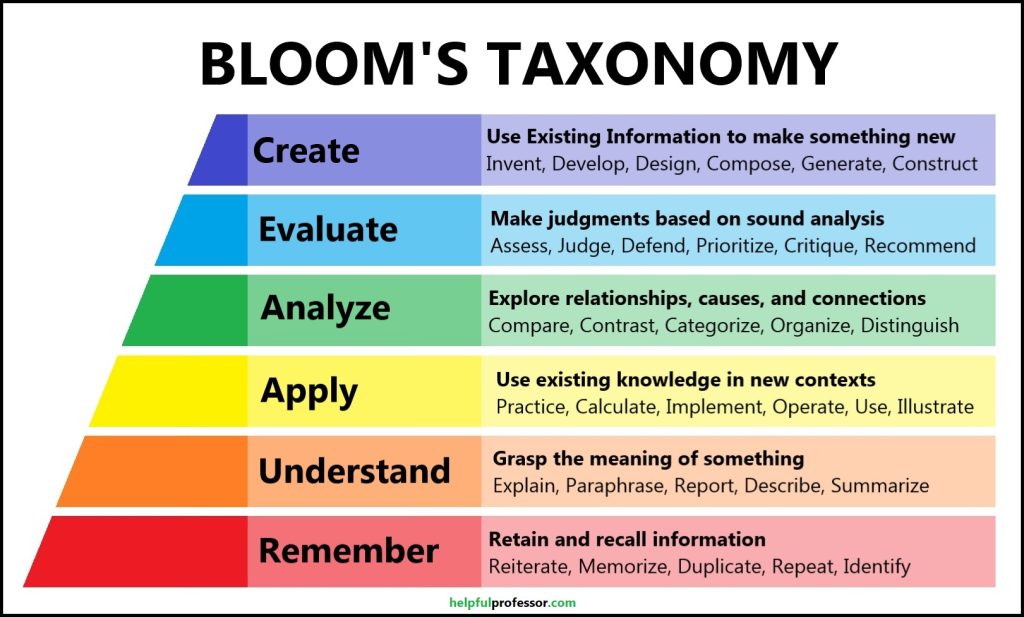

There are multiple frameworks for writing behavioral objectives. The two most common are Bloom’s Taxonomy and the SOLO Taxonomy.

Traditionally, we would write educational objectives using Bloom’s Taxonomy. This is a hierarchy that ranks verbs describing educational objectives from low-level to high-level understanding.

| Bloom’s Taxonomy Level | Action Verbs |

| 1. Remembering | Define, Describe, Identify, List, Label, Memorize, Name, Outline, Recall, Recognize, Reproduce, State, Match, Repeat |

| 2. Understanding | Classify, Compare, Contrast, Demonstrate, Discuss, Explain, Express, Illustrate, Indicate, Interpret, Paraphrase, Predict, Relate, Report, Restate, Review, Summarize, Translate, Associate, Distinguish, Extend, Generalize, Infer, Represent, Sort |

| 3. Applying | Apply, Choose, Compute, Construct, Dramatize, Employ, Illustrate, Interpret, Manipulate, Modify, Operate, Practice, Schedule, Sketch, Solve, Use, Demonstrate, Discover, Implement, Prepare, Produce, Relate, Show, Transfer, Utilize |

| 4. Analyzing | Analyze, Appraise, Break down, Categorize, Compare, Contrast, Criticize, Distinguish, Examine, Experiment, Identify, Infer, Inspect, Motivate, Question, Test, Detect, Diagram, Discriminate, Dissect, Estimate, Evaluate, Explain, Explore, Separate |

| 5. Evaluating | Appraise, Argue, Assess, Attach, Choose, Compare, Conclude, Contrast, Criticize, Debate, Decide, Defend, Estimate, Evaluate, Explain, Interpret, Judge, Justify, Measure, Rank, Rate, Recommend, Review, Select, Support, Validate |

| 6. Creating | Arrange, Assemble, Collect, Compose, Construct, Create, Design, Develop, Formulate, Generate, Invent, Make, Organize, Plan, Prepare, Produce, Propose, Set up, Synthesize, Write, Combine, Compile, Conceive, Construct, Create, Design, Devise, Initiate, Integrate, Rearrange |

Based on these verbs, we could create learning objectives stratified by grade.

For example, we may have this as the core learning objective:

“Students will explore themes and symbolism in a given literary text”, we can

The behavioral objectives that will determine a student’s grade may be stratified based on Bloom’s taxonomy:

| Grade | Descriptor | Verbs Used |

| A (Evaluation Skill) | The student will be able to critically assess the effectiveness of themes and symbolism in the literary text and justify their interpretations and opinions with strong evidence from the text. | Critically assess, justify |

| B (Analysis Skill) | The student will be able to examine themes and symbolism in the literary text, identifying their relationships and implications, and distinguish between various literary elements and techniques used by the author. | Identify relationships and implications, distinguish between |

| C (Application Skill) | The student will be able to identify themes and symbolism in the literary text, explain their relevance to the overall message, and apply knowledge of literary elements and techniques to support their interpretation of the text. | Apply knowledge, support their interpretation |

| D (Understanding) | The student will be able to recognize basic themes and symbolism present in the literary text and describe the main ideas and events of the text in their own words. | Recognize, describe |

A core limitation of Bloom’s Taxonomy is that it sometimes doesn’t describe observable behaviors but rather skills. The SOLO Taxonomy by John Biggs addresses this concern.

SOLO Taxonomy stands for Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome. This model is designed to provide a framework for describing observable behavioral objectives.

Observable objectives, Biggs argues, are easier to grade because you can see the behavioral objectives you are aiming to assess.

Biggs names the levels of learning complexity (from lowest to highest complexity) prestructural, unistructural, multistructutral, relational, and extended abstract.

(Note: While I won’t go into the meaning of each level of complexity here, you can read my guide on Biggs’s levels of learning complexity here to get a deeper understanding of each level.

| SOLO Taxonomy Level | Action Verbs |

| 1. Prestructural | List, Recall, Name, Define, Recognize |

| 2. Unistructural | Describe, Explain, Summarize, Illustrate, Paraphrase, Report, Define, Express, Perform, State |

| 3. Multistructural | Compare, Contrast, Categorize, Classify, Sequence, Order, Arrange, Combine, Separate, Differentiate |

| 4. Relational | Synthesize, Predict, Reflect, Theorize, Deduce, Organize, Create, Construct, Examine, Illustrate, Link, Formulate, Plan, Produce, Solve, Design, Develop, Relate, Connect, Distinguish, Discriminate, Correlate, Elaborate |

| 5. Extended abstract | Create, Design, Construct, Invent, Project, Extrapolate, Reconstruct, Reorganize, Transform, Extend, Modify, Propose, Critique, Appraise, Revise, Reevaluate, Conceptualize |

Clearly, there are many overlaps with Bloom’s taxonomy here, but one key takeaway is that the verbs in the SOLO taxonomy tend to describe more observable behaviors rather than simply skills.

Not only do educators and professional trainers need well-defined behavioral objectives, but students do too.

The SMART goals framework is a template for students to help them define behavioral objectives related to their educational or career goals.

There are 5 components.

Example: I will use flash cards to learn 15 new Spanish words each week for the next month.

This example is specific, realistic, measurable, and identifies a time-frame.

For more SMART Goals for students, visit our detailed list of SMART goals.

Behavioral objectives refer to defining specific learning outcomes in terms of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills.

Behavioral objectives are used in a variety of contexts, from education to professional development training.

Guidelines for how to construct well-defined objectives suggest that they be specific, measurable, and time-based.

Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives provides a useful framework for how to organize behavioral objectives.

Rubrics offer another template for organizing objectives that also allow students to form a better understanding of grading criteria and improve their performance.

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. A. (2001). Taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Dawson, P. (2017). Assessment rubrics: Towards clearer and more replicable design, research and practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 347-360.

Jonsson, A., & Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), 130–144.

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Book II. Affective domain. New York, NY. David McKay Company, Inc.

Tyler, R. W. (2013). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. University of Chicago press.

Wu, W. H., Kao, H. Y., Wu, S. H., & Wei, C. W. (2019). Development and evaluation of affective domain using student’s feedback in entrepreneurial Massive Open Online Courses. Frontiers in Psychology, 1109.